Dear Oliver,

December is an important month in the history of tea in the “New World” as early

Europeans dubbed the lands across the Atlantic. These early settlers were reliant

on European goods and services for many of the staples that they were

accustomed to using and enjoying in their daily lives. Tea was one of the valuable

commodities primarily traded by the East India Company.

By 1773, the East India Company had a virtual monopoly on tea shipped to the

colonies, which was set in place by British Parliament in the Tea Act. This act

granted the company preferred status and a monopoly on tea exports to the

colonies, exemption on export taxes, and refunds on certain surplus teas. All this

cut out independent colonial shippers and merchants.

According to the Britannica Online Encyclopedia, this “...drove the normally

conservative colonial merchants into an alliance with radicals led by Samuel

Adams and his Sons of Liberty. In such cities as New York, Philadelphia, and

Charleston, tea agents resigned or canceled orders, and merchants refused

consignments. In Boston, however, the royal governor Thomas Hutchinson

determined to uphold the law and maintained that three arriving ships, the

Dartmouth, Eleanor, and Beaver should be allowed to deposit their cargoes and

that appropriate duties should be honored.” Another ship, the William, was also

destined for Boston but had run aground in Cape Cod.

Interestingly, all the additional cargo from the ships that reached Boston was

allowed by authorities and unloaded except the tea, which was left floating in the

harbor. Efforts were made by Patriots such as Adams to return the tea, but

Governor Hutchinson refused.

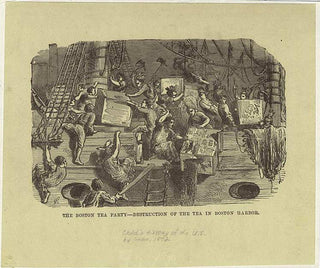

This decision in Massachusetts led to the bold act that is now widely known as

“The Boston Tea Party.” On December 16, 1773 at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston, a

group of local men covered in blankets and wearing Native American headdresses boarded these three ships and dumped the contents of the tea chests into the sea.

Not surprisingly, British Parliament was outraged and quickly passed the

“Coercive Acts.” The unhappy colonists changed this to the “Intolerable Acts,”

which effectively shut off all sea trade to the area until reimbursement for the lost

tea was made. This was a pivotal moment that served to unite the colonies in the

quest for independence.

Charleston, S.C. in 1780, published c. 1850 by G.P. Putnam, New York. From the collections of the South Carolina Historical Society.

As stated, Boston was not the only city receiving tea from the East India Company. Oliver Pluff’s home city of Charles Town (Charleston) was also involved in the December drama. Another chapter of the Colonies’ Sons of Liberty was located there and local Patriot Christopher Gadsden initiated efforts to refuse a tea shipment arriving on the London days earlier on December 1, 1773.

Ultimately, this shipment was unloaded and locked away in the basement of the

city’s Old Exchange building and the London sailed on for New York. This,

however, was a less than perfect solution. Joseph Cummins writes in the book

“Ten Tea Parties,” that “the British were not entirely unhappy with this

resolution.” And, the Charleston Tea Party was “not equal in criminality to the

proceedings in other Colonies.” This sentiment did little to ease tensions in

Charles Town where Gadsden and others learned that Charles Town was the only

port that had accepted the tea. Furthermore, it was now being sold in the area.

During this time, Gadsden initiated an effort to eliminate tea usage in the region,

but this proved futile as households began hoarding and buying any tea they

could access. Charlestonians were not ready to give up tea.

Meanwhile, the Coercive Acts proved just as unpopular to other colonies as in

Boston and thus set the stage for massive agreement with various colonial leaders and membership in the Sons of Liberty swelled. Charlestonians supported

Boston’s boycott and sent food to their northern neighbors, but did not initially

boycott all European vessels.

HMS Britannia in Charleston Harbor, painting by George Hyde Chambers, 1834

Finally, in 1774 after a ship called Magna Carta twice arrived in the port carrying

tea, did Charlestonians, according to Cummins, get serious about a widespread

tea boycott. So, along with the other large cities and smaller colonial towns such

as Chestertown, York, Annapolis, Edenton, Wilmington, and Greenwich – tea took

its place in history leading to the Revolutionary War.

For more detailed information, earlier Oliver Pluff blog posts such as the March 7-

9 histories detail much of Charleston’s early tea experience. These include local

newspaper accounts and first-hand information about the early role of tea in the

area. In addition, the tab History of Tea includes local Charleston information as

well.

Tea’s popularity hasn’t waned in the following centuries. Currently, according to

the online site Statista, on average, every American consumed 430 grams or almost a pound of tea a piece in 2022. That translates to more than $13 billion spent in 2021 on tea. These numbers make the United States the leading tea importer and much tea still arrives in the giant sea-going vessels of today. According to U.S. Customs, tea imports are currently tax free (although other fees are charged.) Additionally, residents can personally bring any amount of leaf tea into the country with them as long as it is declared upon arrival.

According to a 2014 article in The Washington Post, “Americans favorite kind is black tea, which accounts for more than half of all tea consumed in the country.”

One big difference in the current American appetite for tea that strays from the

country’s early roots, is the preference of iced tea as well as the traditional hot

varieties. And, unlike elaborate tea rituals of the past, convenience is the name of

the game as well. Premade, prebagged, or served as takeout, tea is here to stay

and ready to go!